Service design is a controversial and elusive discipline. I started my PhD thinking I was doing—and about to study—Service Design. Right now, I’m not so sure.

Many people understand service design by thinking of its most famous tool: the Service Blueprint. It was initially proposed by G. Lynn Shostack as an operational tool to design services that deliver1. The most well-known service design tool was proposed by a marketer in a business journal, which makes the case for suspicion—is it designerly enough? Service blueprint is ubiquitous, there are even whole publications dedicated to it. Cameron Tonkinwise argues we need to rethink this tool, go read it. Among other things, he questions one of the foundations of the service blueprint, the line of visibility:

A defining element of the Service Blueprint, what differentiates it from a Customer Journey Map, is the ‘Line of Visibility.’ This straight line divides Blueprint canvases into a top part representing the ‘front-stage’ in which the service recipient interacts with the service system’s touchpoints, which includes the ‘front-line’ customer service worker, from the ‘back office’ operations.

The Line of Visibility seems natural, but designers should always question such assumptions. Why do aspects of the service need to be concealed beneath a Line of Visibility?2

The line of visibility divides the service between the front stage and the backstage. The theatre metaphor is largely used in service design as if we were all creating this performance, putting on masks to enact some kind of magic whose tricks are carefully hidden under this line of visibility. Much of the service designer’s work is related to making the invisible visible. Many practitioners and academics reflect on this regularly.

Josina Vink proposes a framework for making the invisible social structures visible, the iceberg framework.3

Vink moves the line of visibility from the stage metaphor and brings it to the vast ocean, shifting the focus from what is purposefully being hidden to that which supports what’s visible: the huge and unknown mass of the underlying social structures. The iceberg is more dangerous, less manageable.

Where’s the force?

Josina Vink produces incredible visualisations and metaphors for complex concepts, and I believe the iceberg is one of those.

However, this idea of a line of visibility, both on the iceberg and on the service blueprint, is too stable, maybe too simple. It’s static. Social structures are not static, the kind of action they perform in designing is probably better described as a force. I can think of pressure, gravity, centrifugation, inertia…

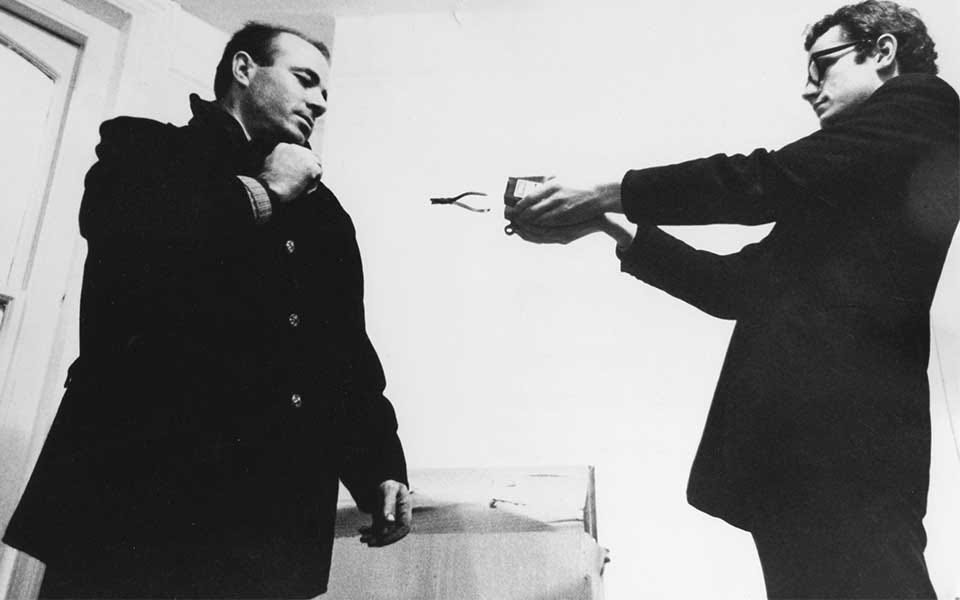

Someone who knew a great deal about forces is Takis. Takis was a Greek artist whose work is partly invisible. Takis worked with light, sound, and movement. He worked with energy.4

There was a Takis exhibition in Barcelona in 2019, right when I was reflecting on the idea of invisibility. Takis makes energy visible in the blank space between the apparently floating objects. He doesn’t need a line of visibility, he leaves the doors wide open so we can delve into his creations and sense the invisible energy keeping them together.

When designing, there are many understandings of invisibility:

The work itself.5

The hidden social structures (which, according to Vink, are the object of service ecosystem design).

The purposefully hidden (service) elements.

Lines of visibility are suitable for representing what we wish would happen in a mechanically working backstage—service blueprint—and are also good for describing what’s underneath physical enactments, that-which-we-can-see.

But we need to act upon it. Make things happen.

Thinking about the forces prompts us to keep moving to avoid becoming trapped in description. Forces are inevitable, they pressure us, push us, they bother us. They can also trigger us to act. Designing with and against forces calls for constant movement, ongoing work.

Takis gave me the poetics to describe my praxis, he rendered the constant struggle and balance of different types of forces and energies visible. Beautifully.

It’s good to think we can still, hence must, propose new metaphors.

How invigorating.

Shostack, G. L. (1984). Designing Services That Deliver. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/1984/01/designing-services-that-deliver

Tonkinwise, C. (2023). Hacking Service Blueprints. Medium. https://medium.com/@camerontw/hacking-service-blueprints-d1fcc526138e

Vink, J., & Koskela-Huotari, K. (2021). Social Structures as Service Design Materials. International Journal of Design, 15(3), 29–43. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/357579146_Social_Structures_as_Service_Design_Materials

Brett, G., & Wellen, M. (Eds.). (2019). Takis. MACBA Museu d’Art Contemporani de Barcelona.

See my previous post on designing: